If Google were a country, its 2019 revenue of $162 billion would make it the 60th largest economy in terms of GDP, surpassing 135 smaller countries, according to IMF data.

Considering that Google had 118,899 full-time employees as of Dec 2019, its $162 billion revenue translates to a GDP per capita of $1.36 million.

(You get GDP per capita by dividing a country’s economic output by its population).

In Q4 2019, the United States of America had a GDP per capita of $65.420. Comparing the GDP per capita of a country to the GDP per capita of a company is by no means an apple to apple comparison.

But the comparison throws light on two points:

1. Google is way BIGGER than you, and I imagine ( It operates 69 consumer-facing products, 29 for business products & 13 for developer products )

2. The per capita contribution of knowledge workers is way more than that of non-knowledge workers, skewing the earlier comparison.

When I decided to cover Google’s Business Model, I thought it would be relatively easy because I make a living by running Google ads. ( the one revenue stream we all know about ).

It turns out, I was wrong. Google has many products that deserve an entire piece to itself. I will cover note-worthy products separately (already covered YouTube), but this one will be about the whole of Google and more.

More because Google became an Alphabet subsidiary after undergoing corporate restructuring in 2015.

And it is essential to understand Alphabet to be able to see the broader vision and Google’s role in it. Keeping that aside, for now, it would be unwise to learn about Google’s business model without first walking through significant events in the history of Google.

What I’m going to do is run you through all of them, and then, when we look into the income streams after that, they’ll make much more sense.

Let’s dive right in. It’s going to be a long ride (5,091 words to be precise), so sit tight.

Last mover advantage

When students go to business school, one of the concepts they’re taught is the first-mover advantage.

The first one to enter a market gains benefits like establishing a strong brand presence, developing customer loyalty & achieving economies of scale — even before competitors enter the market, and retain those advantages for a long time, in many cases.

But when Google launched in 1998, there was no first-mover advantage up for the taking.

Incumbents like Yahoo, Excite, Altavista, and others ruled the search engine market. While search results weren’t as relevant, the general assumption was that the problem had been solved as well as possible.

Steven Levy, an acclaimed tech journalist who wrote the book ‘In the Plex: How Google Thinks, Works, and Shapes Our Lives‘, recalls a rough statement made by one of Alta Vista’s engineers about the problem of search in 1996,

“It’s not a science. It’s an art, sort of mystical hits & misses. We’ve solved the problems. Now it’s just basically the artistry part that remains”

Google’s last mover advantage was that Sergey Brin & Larry Page challenged the existing assumption.

Larry & Sergey, the heroes of our story, met each other at the Stanford University. Sergey was enrolled in the computer science master’s program at the time & Larry was pursuing a Computer Science PhD.

Larry came across the insight that would change the internet while pondering the web’s link structure as part of his PhD.

( We’re now going to learn about the first version of Google’s algorithm. It still serves as a major ranking factor, for Google as well as smaller competitors like Bing, Yahoo, Baidu, Yandex & DuckDuckgo )

Say Page A linked to Page B, C, D. While outbound links ( B, C, D) were known because they were visible on A, there was no way to find inbound links to A ( Inbound links to A need not necessarily be from B, C & D; they would in most cases come from different pages like from X, Y & Z).

Larry thought it would be useful to know which pages were linking back to A, and more critically, understanding the authority of pages linking back to A, based on various factors of the backlinking site.

The count of pages linking back and authority each link carried would help determine the rank of Page A. Dubbed PageRank, Larry & Sergey developed an algorithm that took both these factors into account to rank pages.

The explanation is, of course, a simplified version of a sophisticated algorithm.

In August 1996, Larry & Sergey released the first version of Google. And the search results were way better than the incumbent search engines of the time, most of which ranked pages based on the number of times the search term appeared on the web page ( an easily hackable system ).

Failed Attempts of Selling Google

In the early days, Larry & Sergey tried to license the search technology but failed, so they continued improving the product.

By Sep 1998, the Google search engine had turned into a hot commodity.

Andy Bechtolsheim, the co-founder of Sun Microsystems, was so impressed after a quick demo, he told the founders,

“Instead of us discussing all the details, why don’t I just write you a check?”

In 1998, after receiving an angel funding of $100,000 from Andy Bechtolsheim, Google was incorporated as a company. More funds, $900,000 to be precise, rolled in soon in the form of initial funding.

The next year, 1999, turned out to be eventful in the history of Search Engines. Not only did Google upgrade from Beta to launch officially (it was handling 10,000 search queries a day), both Excite & Yahoo turned down buying Google for a paltry $1 Million.

In his memoir, Jeremy Ring, a top sales at Yahoo from 1996 to 2001, lamented over the missed opportunity saying,

“That $1 million price tag was probably the best deal offered in the history of Silicon Valley, California, the United States, planet Earth, and the Milky Way Galaxy.”

In 2002, Yahoo had another shot at buying Google. Yahoo was willing to pay $3 Million, but Google was unwilling to settle for less than $5 Million.

Laying the foundations of a billion-dollar digital advertising empire

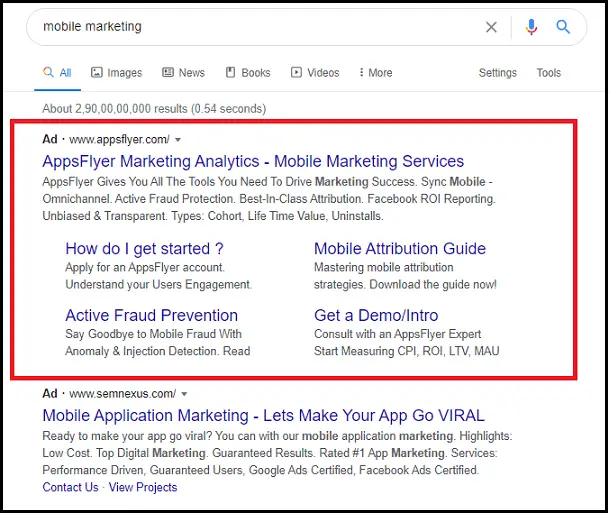

Google Search ads

Google’s original monetization plan included three different revenue streams: licensing its superior quality search results to Yahoo & Altavista, customized search for businesses & advertising.

They expected advertising to make up for around 10 to 15 percent of the total. But the ad business grew way beyond expectations, and the three-pronged approach turned into an ad-centric business.

Google began with text-based search ads. And since search ads were relevant to what people were looking for, they were effective. But AdWords still charged advertisers based on CPM ( cost per thousand impressions ), which was the basis of all existing ad markets.

At the time, GoTo, one of Google’s competitors, used a different system, charging advertisers for clicks, not impressions (because someone clicking on an ad is more valuable than someone seeing it).

Instead of predetermined prices for ad spots, GoTo used an auction-based model, wherein an advertiser had to outbid other advertisers, to win the top spot.

Drawing inspiration from Goto’s ad system, Google pivoted to charging advertisers for clicks and the auction-based system, sprinkling the auction with a twist that made it better.

GoTo’s auction worked like a traditional auction. But Eric Veach, the computer scientist, who played a crucial role in developing the AdWords auction system, had a different point of view.

He thought it was nonsensical that advertisers were bound to pay their bid amount, even if the next lowest bidder bid significantly less.

While the traditional auction methodology worked in one time, commodity auctions, it wasn’t ideal for a recurring, ad-based auction. It created a dynamic where advertisers always had an incentive to lower their bids.

So, Eric devised a better model where the auction winners wouldn’t pay the amount of their winning bid. Instead, the winner would pay only a penny more than the runner-up’s bid, incentivizing them to bid higher. This way, the winner would also not have to worry about

paying more wastefully.

For example, imagine we have three advertisers called A, B & C. If A bids 15 cents a click, B bids 6, and C bids 1, A wins the first slot and only pays 7. B wins the second spot and pays 2.

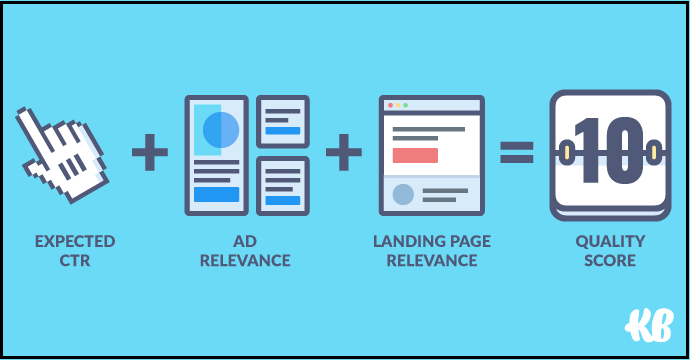

Google added more finesse to the auction system with another innovation. Advertiser bids would only be half of what ultimately determined the auction winner. The other half would be a metric called quality score, which measured how relevant the ad was to the user’s quest.

In the early days, Google used click-through rates ( the ratio of how many users clicked the ad divided by how many saw users the ad ) to determine the quality score.

Later, they added two more variables to the quality score formula: the relevance of the ad to the specific keyword and the quality of the landing page.

Sherly Sandberg, now Facebook COO, who was then with Google at the time, beautifully described the usefulness of the quality score formula,

“It made the advertiser do the work to be relevant. You paid less if your ads were more relevant. So you had a reason to work on your keyword, your text, your landing page, and generally improve your campaign.”

In January 2002, Google tested the new Adwords by offering it to a few advertisers. Once it received positive validation from the test group, Adwords was rolled out for all advertisers. The program became such a hit that 2002 became Google’s first Profitable year.

Google Adsense

Adwords soon got a partner in the form of what is today known as Google Adsense. The idea of putting ads on third-party web pages had been floating around for a long time.

Google already had the Adwords recipe; all that was needed were some new ingredients.

Two of Google’s best engineers, Harik & Shazeer, developed a system that would match keywords to web pages. If a web page were full of information about scuba diving, it would extract keywords like “scuba diving gear,” “scuba diving locations,” and “scuba diving mask.”

Using the system’s ability to understand the content of a page, Google could determine what kind of banner ads would be ideal alongside a particular web page.

Until then, Google’s ability to place ads was restricted to its search results. But the new system would turn the whole web into Google’s ad canvas, changing the economics of the web.

Existing, big publishers, as well as upcoming, smaller creators, would be able to monetize their content. Google’s system would handle ad selling, and in exchange for that, ad revenue would be split between Google and program partners.

But in 2003, around the same time, a startup called Applied Semantics had patented technology that understood, organized, and extracted knowledge from websites. The technology was used in a product called Adsense that analyzed web pages and extracted key themes to place relevant ads.

Adsense was similar to what Google wanted to do, and the patent could have been a problem. Luckily, for Google, the founders of Applied Semantics were open to the idea of selling.

Google acquired Applied Semantics for $42 Million & 1 percent of its stock, adopted the name Adsense & launched the offering to advertisers.

Much like Adwords, Adsense was a hit. It accounted for an estimated 15 percent of Google’s total revenues by early 2005. For Google, the company, Adsense’s success mattered because it proved the company could make money outside of search ads, its core business.

Gokul Rajaram, then Adsense product manager, expressed its business importance saying,

“You can think of the search engine as the crown jewel of Google. With a program like AdSense, Google was able to make money from its partners—it was kind of a moat that protects the king’s castle.”

Google Analytics

After Adwords & Adsense, the next significant product was Analytics, building a powerful trilogy.

Advertisers used Adwords to buy ads on Google Search result, and Adsense to buy display banners on websites partnered with Google.

Using Analytics, anyone, including advertisers, could track and measure website activity — how many people visited, which websites referred them back, and of course, how many users performed a valuable action like buying something via a Google ad.

One of the engineers named Chan originally came up with the idea for Analytics. But due to resource constraints, Google decided to acquire a similar existing service called Urchin for $20 Million in Late 2004. Urchin then became Google Analytics.

The original idea was to charge $500 a month for the service and offer special discounts to Adwords customers. But Google decided to release for free because it would indirectly increase adoption of Adwords & Adsense. The more efficiently advertisers could track metrics, the more they were likely to use Adwords & Adsense.

When Google Analytics went live in November 2005, virtually all of Google’s servers crashed despite Chan having provisioned data centers for the overload.

Eric Schmidt, then Google CEO, later referred to the event as Google’s most successful disaster.

Expanding the reach of the Advertising Empire

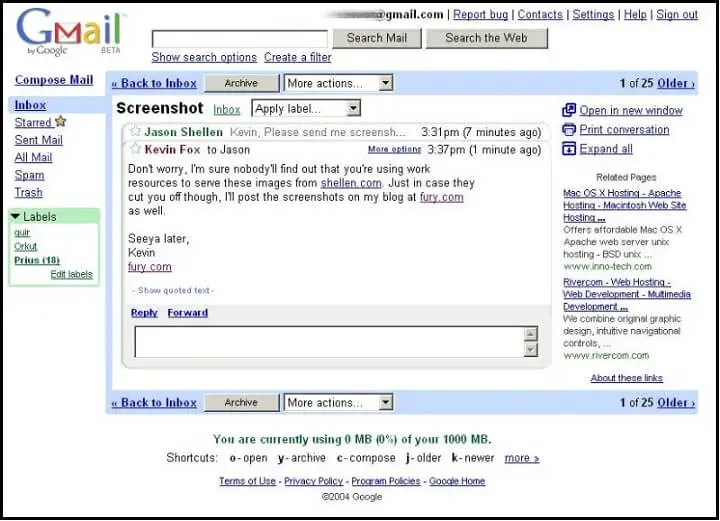

Gmail & Chrome

With Adwords, Adsense & Analytics, Google had laid a strong foundation of its Ad empire. But it still had to protect and expand its ad empire, which it did, either by acquiring products or developing them internally.

Gmail and Chrome were both developed internally, both of which were substantial improvements over existing solutions.

When Google launched Gmail in 2004, Microsoft’s Hotmail was the existing incumbent. But Hotmail came with a limited storage capacity of 2MB. ( This was, of course, before the cloud era began officially )

When Gmail launched on 1st April 2004 with an announcement that the service would come with a storage capacity of 1 GB — 500 times of what Microsoft’s Hotmail offered, everybody thought it was a joke. But Google was serious, even though it purposefully chose April fool’s day to make people suspicious.

Over the years, free storage space kept increasing. At the time of writing, Google offers 15 GB of free storage shared across various products, including Gmail, Drive, Photos, and more.

With more than 1.8 billion users in 2020, Gmail is the most widely used email service worldwide. Or to put it another way, Google provides free email service to 1.8 billion users, monetizing their attention by showing them ads while using the service.

While Gmail’s promise was more storage space, Chrome was about speeding up the browser.

The faster the browser, the more searches, and more searches meant more ads & money. In the future, it would mean enviable access to user data & increased control over the search ecosystem.

While Google is the default search engine on Chrome, it pays Apple north of $7 billion annually to be the default search engine on iOS.

Chrome was not just an incremental improvement to existing incumbents like Mozilla and Firefox — it was 56 times faster than Internet Explorer at the time of launch.

By the end of 2010, around two years after its launch in Sep 2008, Chrome had more than 120 million users.

At the time of writing, Chrome dominates the browser market with a market share of 65.89%. Safari comes second with a market share of 16.65%.

YouTube

Post the text-based search revolution, the web was in dire need of a video hub, and Google wasn’t blind to the opportunity. Google put together a team in 2003 to work on a project called Google Video.

The idea was to either license professionally produced content in categories like television news & shows, sports, documentaries, movies, or make it available for free and support it using advertising.

But Google Video failed to grow as quickly as YouTube, a startup founded by three ex-PayPal employees.

YouTube benefitted from user-generated content and an initially lax policy on copyrighted content ( users uploaded truckloads of copyrighted content ). In some ways, YouTube had become a video version of Google search.

By the time Google Video pivoted to allowing users to upload self-generated content, YouTube has already won the race. So, Google decided to buy the winning trophy with purposeful exuberance.

Eric Schmidt, then Google CEO, admitted that YouTube wasn’t worth the $1.65 Billion Google paid to acquire it, explaining the rationale behind paying $1 Billion more than what he thought YouTube was worth at the time,

“Sure, this is a company with very little revenue, growing quickly with user adoption, growing much faster than Google Video, which was the product that Google had. And they had indicated to us that they would be sold, and we believed that there would be a competing offer—because of who Google was—paying much more than they were worth. In the deal dynamics, the price, remember, is not set by my judgment or by financial model or discounted cash flow. It’s set by what people are willing to pay. And we ultimately concluded that $1.65 billion included a premium for moving quickly and making sure that we could participate in the user success in YouTube.”

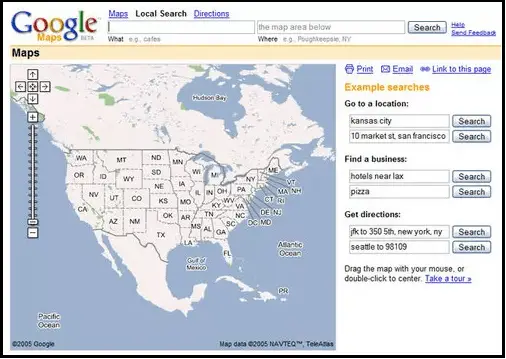

Maps

From the beginning, Google’s mission was to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Sticking to the mission meant going further than indexing the web — encompassing taking the real world’ physical information and democratizing it.

But Google wasn’t the first to launch online maps; seeing competitors race ahead made them foray into online mapping.

They strengthened internal efforts by acquiring three startups: Where 2 Technologies, Keyhole & Zipdash. Post-acquisition, all three companies worked together on building Google Maps.

At the time of writing, Google has more than 1 billion users monthly active users & more than 5 million websites and apps use the Google Maps API.

Just like Gmail, Google primarily uses ads to monetize Maps. Apart from that, third-party websites and apps also pay for Google Maps integration, depending upon their usage.

DoubleClick

In 2007, Google acquired DoubleClick for $3.1 Billion, almost double what it had paid for YouTube a year ago.

While Adsense was raking in money, Google was not dominating the display ad market. DoubleClick was the top display network at the time because of its superior user tracking technology.

Unlike Adsense, which served contextual display ads based on the content of the website the user was visiting, DoubleClick used cookies to identify & store the user’s browsing history, making their display ads more relevant.

For example, if you visited a travel blog, you might see an Adsense ad for a trekking backpack that might or might not interest you.

But if you visited travel blogs all the time, the DoubleClick cookie would serve a travel tour banner even when you were on a sports website.

The fact that Microsoft also coveted DoubleClick superior ad tech led to a bidding war, pushing Google to pay $3.1 Billion. For Google, it wasn’t just about winning the prize but also keeping competition away from it.

The Mobile Revolution

Android, Google PlayStore, Google Admob, & Google Phones

The PC revolution, which roughly started around the 1980s, was dominated by Mircosoft’s Windows operating system in the initial 25 odd years.

In terms of hardware, the evolution from desktops to laptops happened over a longer horizon relative to laptops’ transition to mobile.

And by the early 2000s, it had become clear to many, including Google, that the digital world would soon be mobile-first.

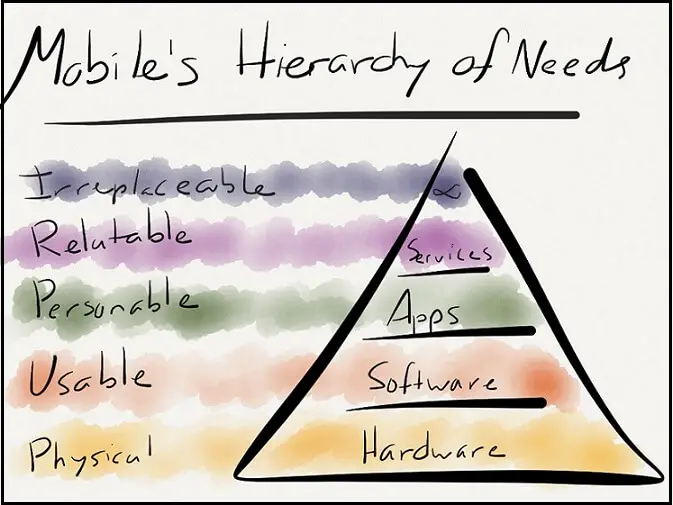

To understand Google’s response to the mobile-first economy, we need to understand a framework called Mobile’s Hierarchy of needs.

The most critical component of the phone is, of course, the hardware. Without hardware, the software ( think operating system ) will be useless.

Once the hardware and software are in place, smartphones can be made more productive by integrating default services like email, maps, app stores, etc.

Users can choose which apps to download from the app store, but their choices are limited by the apps available ( Not all android apps have an iOS version. Similarly, some iOS apps don’t have android versions )

The hardware, software, services & apps make up the entire mobile ecosystem. And how much control you have over it depends on the layers you control.

Google’s acquisition of android in 2005 made sure it had a certain degree of control over the software and the layers above it.

Just like iOS phones come with pre-installed Apple apps like Facetime, Apple Maps, Apple Appstore, etc.; android phones come with pre-installed with Google Apps like Gmail, Google Maps, and Google Playstore, etc.

Being the default app store also comes with the advantage of collecting a commission on all in-app purchases ( Both Google & Apple take a 30% cut on sales )

If you think deeply about the mobile hierarchy of needs, it also makes sense for Google to own the hardware. Owning the hardware gives Google unparalleled freedom to package its products and service as a whole, which is why, despite not having achieved much success on the smartphone front, Google refuses to give up.

Google also bought a chunk of HTC’s smartphone division for $1.1 Billion in 2017, but it has not established anything close to a dominant smartphone market position yet.

Apart from android, play store, and phones, one of the lesser-known Google mobile move is Admob, a mobile advertising company it acquired for $750 Million, which helped it cement its position in the mobile advertising market.

Cloud Computing

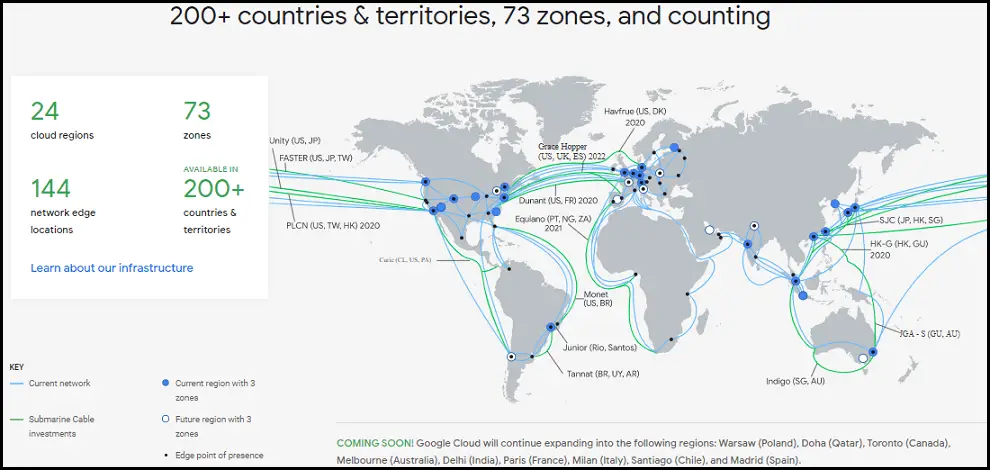

When you talk about Cloud, the first thing that comes up in almost everybody’s mind is AWS, and rightly so, AWS is the leading cloud service provider.

But unlike Amazon, which entered the Cloud market in 2006 with its Infrastructure as a service ( IaaS ) offering, the first public cloud service launched by Google in 2008 was a Platform as a Sevice ( PaaS ), called App Engine.

Google made its entry into the IaaS market in 2010 when it launched cloud service storage. Since then, Google has continued to expand its set of services.

At the time of writing, Google organizes its cloud services in 18 categories, including compute, storage, databases, networking, data analytics & the Internet of Things, to name a few.

In the cloud computing race, Google occupies the third position, after Amazon & Microsoft, with an expected annual revenue run rate of $11 Billion in 2020.

(Revenue run rate is a method used to forecast upcoming earnings over an extended period based on past earnings)

To add perspective, Microsoft, the player occupying the second spot in the cloud race, has an expected annual revenue run rate of $53.2 Billion in 2020.

Google Nest

At the time of writing, Google official mission statement reads,

“Our mission is to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

However, the mission statement lacks much-needed nuance, for which we need to look no further than Google’s October 2019 keynote.

During the keynote, Rick Osterloh, Google Senior Vice President of Devices and Services, termed “Ambient Computing” as the way forward for Google.

“In the mobile era, smartphones changed the world. It’s super useful to have a powerful computer everywhere you are. But it’s even more useful when computing is anywhere you need it, always available to help. Now you heard me talk about this idea with Baratunde, that helpful computing can be all around you — ambient computing. Your devices work together with services and AI, so help is anywhere you want it, and it’s fluid. The technology just fades into the background when you don’t need it. So the devices aren’t the center of the system, you are. That’s our vision for ambient computing.”

Acquired by Google for $3.2 billion in 2014, Nest Labs ( Now Google Nest ) is the piece of the ambient computing puzzle, which ties all of Google’s products and services together. Nest puts Google into our homes, making it closer to us than ever.

But Google’s ambitions don’t end there. Rick Osterloh’s opening statement of the 2019 keynote reveals Google’s plans better,

“If you look across all of Google’s products, from Search to Maps, Gmail to Photos, our mission is to bring a more helpful Google for you. Creating tools that help you increase your knowledge, success, health, and happiness. Now when we apply that mission to hardware and services, it means creating products like Pixel phones, wearables, laptops, and Nest devices for the home. Each one is thoughtfully and responsibly designed to help you day to day without intruding on your life.”

Phew! I agree this was long, but all this context was the bare minimum required before breaking down Google’s business model’s hidden strategy.

Google’s business Model

Google’s business model seems straightforward at the surface level: Advertising is the primary source of revenue. 80.76% of the $182 Billion revenue Google generated in 2019 came from online advertising.

But if you go beyond the surface, there’s more to it than meets the eye.

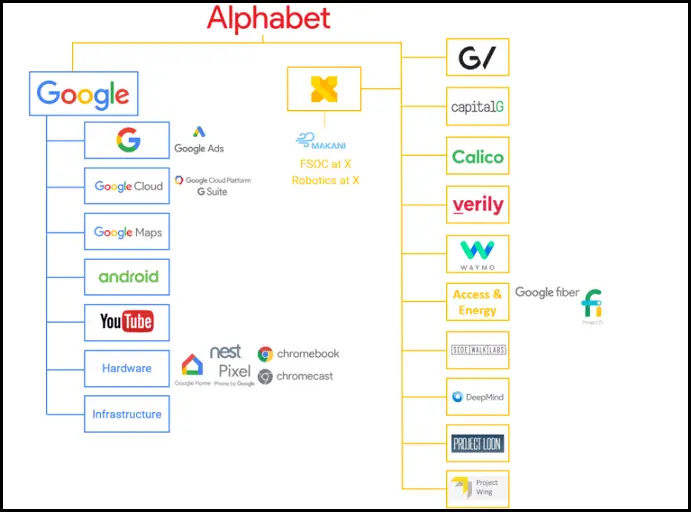

In 2015, Google underwent corporate restructuring, becoming a subsidiary of its parent Alphabet. But what is Alphabet, and why restructuring?

Larry Page, former chief executive of Alphabet (Sundar Pichai heads Alphabet now), shares a somewhat useful answer,

“Alphabet is mostly a collection of companies. The largest of which, of course, is Google. This newer Google is a bit slimmed down, with the companies that are pretty far afield of our main internet products contained in Alphabet instead. What do we mean by far afield? Good examples are our health efforts: Life Sciences (that works on the glucose-sensing contact lens), and Calico (focused on longevity). Fundamentally, we believe this allows us more management scale, as we can run things independently that aren’t very related.”

Other than Google, Alphabet consists of several other subsidiaries collectively referred to as “Other Bets,” which include:

- GV and CapitalG make up Google’s venture capital arm, with investments in companies like Uber, Slack, Glassdoor, etc.

- Waymo is Google’s self-driving car initiative.

- Verily and Calico are healthcare subsidiaries.

- Alphabet Access & Energy house Google’s telecommunications projects and energy initiatives.

- Sidewalk Labs is Google’s attempt at reimagining cities.

- Deepmind, a company Google acquired in 2014, is focussed on AI research.

- Chronicle, a cybersecurity spinoff, builds security solutions for Google’s Cloud Business.

- Project Loon uses balloons to provide internet access in rural areas.

- Project Wing is developing autonomous delivery drones.

- Google X, an R&D facility, works on moonshots: sci-fi sounding technologies.

In the words of Larry Page, “Other Bets” matter because,

“From the start, we’ve always strived to do more, and to do important and meaningful things with the resources we have. We did a lot of things that seemed crazy at the time. Many of those crazy things now have over a billion users, like Google Maps, YouTube, Chrome, and Android. And we haven’t stopped there. We are still trying to do things other people think are crazy but we are super excited about. We’ve long believed that over time companies tend to get comfortable doing the same thing, just making incremental changes. But in the technology industry, where revolutionary ideas drive the next big growth areas, you need to be a bit uncomfortable to stay relevant.”

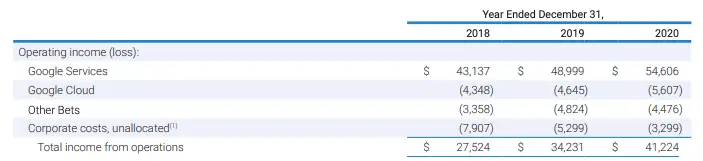

Many of these so-called “Other Bets” might pay off dividends in the future, but at the moment, they don’t contribute positively to the bottom line. Other Bets incurred losses of $3.3 Billion, $4.8 Billion & $4.4 Billion in the years 2018, 2019 & 2020, respectively.

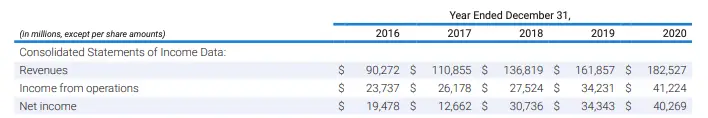

But overall, Alphabet generated a net income of $40 Billion in 2020, up 17% from $34.3 Billion in 2018.

By the end of 2019, the company also had $136 Billion in cash, a pile that has been growing consistently since 2016. Put simply, Alphabet can afford to lose money on “Other Bets” as long as Google, the cash cow, keeps milking.

But what does the revenue distribution look like across different Google properties?

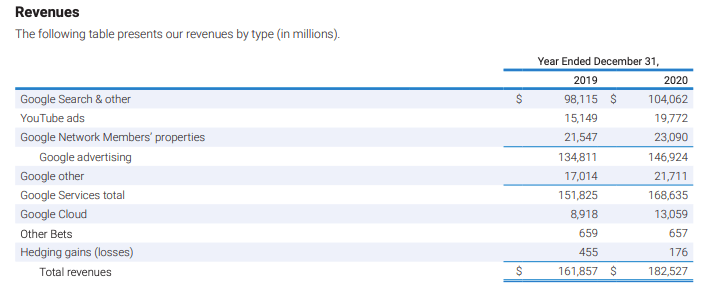

The majority of Google revenue in 2019, around 80% ( $146 B ), came from advertisements on Google-owned properties, including Google Search, Gmail, Google Maps & YouTube.

Around 12.6% ( $23 B) of the revenue came from ads posted on Google Network Members’ properties [ Google Adsense, Google AdMob & Google Ad Manager ( Previously DoubleClick ) ]

Google Cloud, including G Suite productivity tools, accounted for around 7%($13 B) of the revenue.

Revenue from hardware devices (Google Nest home products, Pixelbooks, Pixel phones, and other devices), Google Play Store( In-app purchases & digital content), YouTube Premium, YouTube TV subscriptions & other products and services accounted for the remaining 12% ($22B).

“Other Bets” revenue contribution was less than 1% ( $0.65 B), derived primarily from selling internet & TV services through Access, and Verily’s licensing and R&D services.

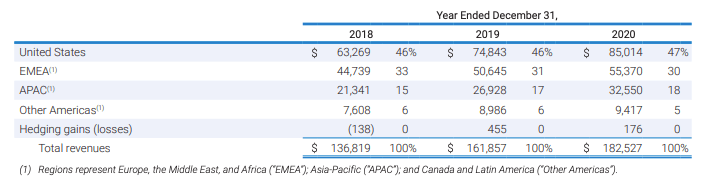

In terms of the region-wise split, revenues from the United States, EMEA, APAC, and Other Americas were $85 billion, $55.3 billion, $32.5 billion, and $9.4 billion.

APAC revenue grew by 52.8% from 2018 to 2020. In the coming years, APAC can be expected to continue as the key growth region for Google.

How to think about Google

To summarize all of it, on the first look, Google seems like an advertising company. But it outgrew just being an advertising company years ago.

One way to think about Google could be that it is a vast AI project that has been fed with data for decades or more, with plans to keep accumulating data and permeating our daily lives as much as possible. But thinking this way would only encapsulate a part of Google’s vision.

Years ago, a Financial Times article (gated access), shared an interesting way of thinking about Google,

“The best comparison for Google seems to me not Microsoft in the 1980s but General Electric in the late 19th century – the age of electrification. Like GE, Google is a multifaceted industrial enterprise riding a wave of technology with an uncanny ability not only to invent far-reaching products but also to produce them commercially.”

The comparison to General Electric undoubtedly sounds strategically romantic, even today, but we need to simplify it.

To me, the right way to think about Google is: “A conglomerate obsessed with pushing the limits of technology, with enough money and ambition to take on challenges few would dream of undertaking, irrespective of the domain or industry.”

Thank you for taking the time to read the entire article. If you liked it, you might also like our article on YouTube’s Business Model.