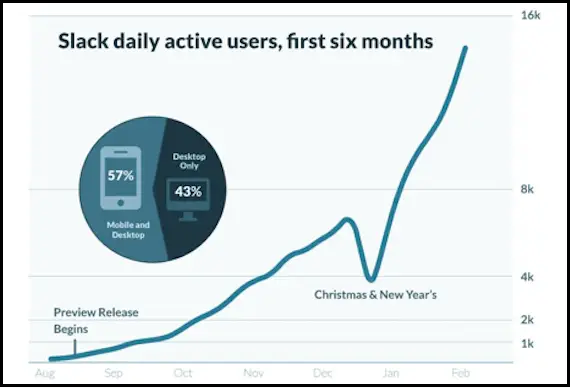

“I have never seen [a] viral enterprise app takeoff like this before — all word of mouth,” tweeted March Andresson in February 2014, six months after Slack launched in preview mode in August 2013. The tweet accompanied a slide from Slack’s investor update deck.

Slack is an embodiment of Silicon Valley’s dream growth trajectory. On the first day of its preview launch itself, 8000 people requested an invitation to try out Slack. Two weeks later, the number had more than doubled to 15000.

In Feb 2014, when Slack dropped the preview and launched officially, around 16000 users were using the service daily. By the end of 2014, Slack had more than 285,000 daily active users — 73 thousand of them paid customers. Five years later, when the company filed for an IPO with the SEC, more than 10 million users worldwide were actively using Slack daily.

Slack has incredible growth metrics, but they give no context into what actually led to the growth in the first place. So, to make sure we don’t miss out on crucial context, let’s go through Slack’s growth story and see how it fits together with the business model.

Slack’s Growth Story

Slack’s founder, Stewart Butterfield, was no startup newbie when he started Slack. Before Slack, he had founded Flickr, one of the first successful photo-sharing sites of all time. Yahoo acquired Flickr for a reported $35 million a little more than a year later after its genesis in February 2004. Stewart’s relationship with Yahoo turned unfruitful after a few years, as it often happens in tech acquisitions, and he resigned in 2008.

Stewart and team didn’t start working on Slack as late as 2012, but one could say that Slack’s seeds were planted when they started building a game called Glitch in 2009. Flickr was born out of a pivot made after Stewart’s original idea of a massively multiplayer online game had failed to get enough traction, so Stewart still had a hunch of building a successful game. And When Stewart left Yahoo in 2008, he had a number of things going for him — money, connections, and a successful track record.

Stewart’s new game, Glitch, attracted tens of thousands of players, but he soon realized it wouldn’t be a commercially viable endeavor. History would repeat itself, and Stewart ended up pivoting from the game to build a completely different product, this time it being Slack. When Stewart pulled the plug on Glitch, the company still had around $5.5 million left out of the $17.5 million raised, and investors who were willing to give him another chance to build a new product.

During its four odd years of existence, Glitch had developed an internal communication tool for its team of employees. This tool, unlike email, helped the team communicate faster and improve internal transparency. Stewart’s thesis was that if the tool helped his team be more productive, it could also help other businesses enhance internal communication.

Slack’s barebones already existed, but the team spent around six months developing the product. For deciding the core features of Slack’s first version, Stewart and the team took inspiration from Paul Buchheit’s famous blog post, “If your product is Great, it doesn’t need to be Good.” Widely known as the creator of Gmail, Paul Buchheit evangelizes a counterintuitive product building philosophy,

“Pick three key attributes or features, get those things very, very right, and then forget about everything else. Those three attributes define the fundamental essence and value of the product — the rest is noise.”

The first version of Gmail exemplified this same philosophy. It had an unimaginable 1 GB email storage when 4MB quotas were the norm, a searchable interface, and threaded conversations.

Paul further argues that “By focusing on only a few core features in the first version, you are forced to find the true essence and value of the product. If your product needs “everything” in order to be good, then it’s probably not very innovative (though it might be a nice upgrade to an existing product).”

In the case of Slack, those three core features were:

Search: Stewart opined that Google had set the standard so high in search that people have certain expectations, and failing to meet these expectations would be fatal. “People need to feel confident that when they read a document or conversation, they don’t have to worry about labeling or storing it — that they’ll be able to find it again later if and when they need it,” Stewart explained.

Synchronization: From the beginning, Slack incorporated “leave-state synchronization” because Stewart and his team had personally experienced the pain of asynchronousness. “One of the things that drove us nuts about every other internal platform,” said Stewart, “was that it was very difficult to pick up in the same place when you switched devices — say, when you left your laptop and picked something back up on your phone.”

File-Sharing: Sharing files is the heart of knowledge work. Slack made sure users could quickly copy-paste images or drag and drop images using a simple, intuitive user interface.

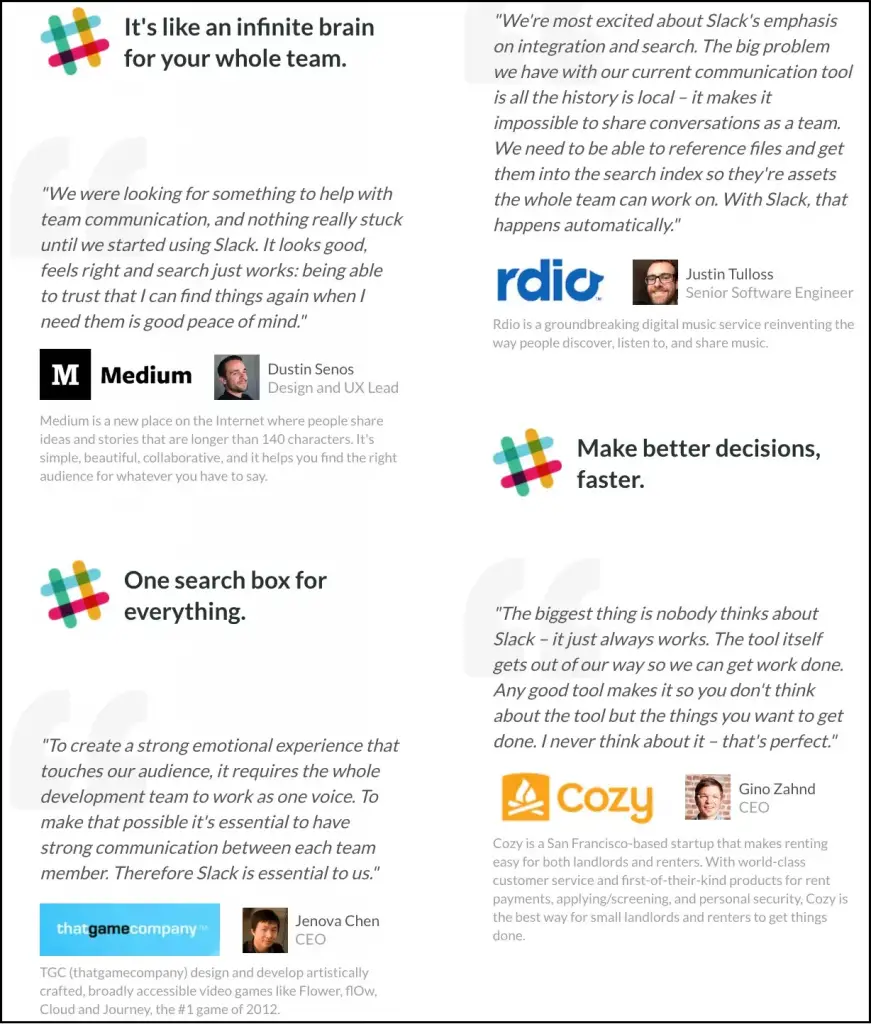

In May 2013, months before the preview release, Butterfield cajoled friends at other companies to try out Slack. Their feedback helped iron out product issues and get testimonials from Stewart’s influential circle at Medium, Rdio, TGC, and Cozy.

Even though PR usually gets a bad rap, it played a crucial role in driving adoption for Slack in its first year. Here are some article headlines from 2013:

- The Co-Founder Of Flickr Wants To Replace Email At The Office” (Business Insider)

- “Flickr Cofounders Launch Slack, An Email Killer” (Fast Company)

- “Flickr founder plans to kill company emails with Slack” (CNET)

These headlines are no doubt clickbaity, and Slack has not killed email to set things straight. But it moved over a lot of communication that traditionally took place over email into this consumer messaging app like tool for enterprises.

And it’s not that people weren’t using chat applications in enterprise settings before Slack came along. But despite the existence of tools like Hipchat, Campfire, or IRC, Stewart shared that only around 20 to 30% of early customers were switching from these messaging applications.

“When we asked the other 70 to 80% what they were using for internal communication, they said, ‘Nothing.’ But obviously they were using something. They just weren’t thinking of this as a category of software.”

When Stewart dug into what was this something that teams were using for communication, he discovered, “It’s a lot of ad hoc emails and mailing lists. Some people on the team might use Hangouts, some use SMS. We see groups that use Skype chat, or even private Facebook groups and Google+ pages.”

This inefficiency in internal communication became Slack’s USP, which positioned itself as a new-age enterprise communication tool that made knowledge workers more productive.

In Dec 2015, Slack launched an App directory with over 150 apps and an $80 million fund to invest in companies that would build Slack apps. Slack’s team developed all of the 150 initial integrations itself, including ones like Google Drive, Github, Stripe & Giphy, to name a few.

The integrations fueled Slack’s daily usage. The app store empowered an army of developers. By the third quarter of 2020, Slack’s app store hosted more than 2400+ apps and was home to a thriving community of 885K+ active developers, some of whom have built sustainable businesses by creating Slack Apps. For example, Donut is a Slack app that helps with employee onboarding and relationship building.

Since its launch in 2013, Slack had been all about communication within an organization. In June 2020, the company launched a new initiative, Slack Connect, to facilitate inter-organization communication. Slack Connect, included in all Slack paid plans, doesn’t bring in extra revenue but creates an additional lock-in for customers. By the end of Q3 2020, more than 64000 paid customers were using Connect.

Slack’s Business Model

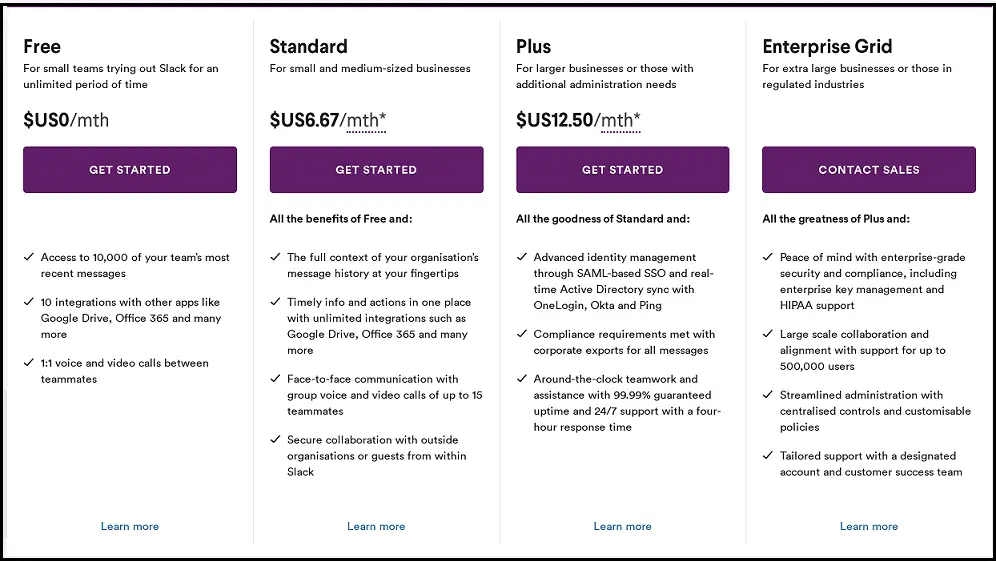

Slack’s offers its basic product for free with some usage restrictions, using the freemium model as a growth lever.

Under its free plan, organizations can only search up to 10,000 of their recent messages. But if you’re a team of, say, ten people generating 2-3k messages per week, you won’t be able to restore any old conversations after approximately a month. Secondly, the free plan allows 1-to-1 video calls, but users can not host group video calls. Thirdly, free users only get access to 10 integrations, limiting their ability to extract value from Slack. Free plan restrictions are structured to move users down the funnel and push them to choose any of Slack’s three paid plans.

More than 750,000 organizations were using Slack until 30th April 2020, the last time the company shared the number publicly. As of 31st October 2020, Slack had more than 142,000 paid customers.

Slack keeps a close eye on two other key business metrics other than paid customers: Paid Customers >$100,000 & Net Dollar Retention rate.

As of 31st January 2019, Slack had 575 customers paying more than $100,000, which accounted for approximately 40% of Slack’s revenue in the fiscal year 2019. By 31st October 2020, the number had almost doubled, with 1,080 customers paying more than $100,000.

For the uninitiated, ‘Net Dollar Retention Rate’ is the percentage of revenue generated from current customers retained from the prior year, after accounting for upgrades, downgrades, and churn. A net dollar retention rate of greater than 100% means growth from the existing customer base more than offset losses from that customer base. As of 31st January 2019, Slack had a net dollar retention rate of 143%.

Slack’s Acquisition

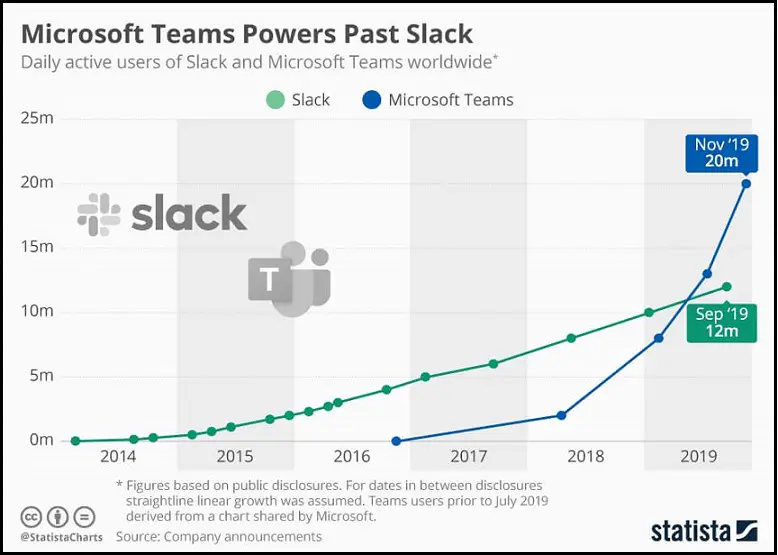

Slack bought a full-page ad in the New York Times to welcome Microsoft when the tech giant launched Teams, a competitor, in 2016.

The open letter, also published on Slack’s blog, was, as one would expect, self-serving. After the customary congratulations, Slack insinuated how Microsoft was a late entrant in a new market, created by Slack.

“We realized a few years ago that the value of switching to Slack was so obvious and the advantages so overwhelming that every business would be using Slack, or “something just like it,” within the decade. It’s validating to see you’ve come around to the same way of thinking.”

In the real-world contest, though, Microsoft raced ahead of Slack in just three years after its launched Teams.

Microsoft was able to beat Slack at its own game because Teams came bundled with Microsoft’s widely used Office 365 suite of products. If a company was already paying more for Office 365, it meant they could use the Slack-like product without paying an extra dime. On the other hand, companies would have to shell out money for using Slack.

On the revenue front, Slack saw growth in revenue despite competition. While still an unprofitable business, Slack made $400.6 million in FY 2019, up 82 percent from $220.5 million in FY 2018. But with losses mounting, going head to head with a tech giant like Microsoft would have been an uphill battle. Fortunately, Salesforce, the cloud-based software giant with deep pockets acquired Slack for $27.7 billion in Dec 2020.

If you liked this piece, you might also like our article covering Discord’s Business Model.